Karate (History of Karate)

(空手) (/kəˈrɑːti/; pronounced [kaɾate] in Japanese ⓘ and [kaɽati] in Okinawan)The martial technique known as karate-do (空手道, Karate-dō) was created in the Ryukyu Kingdom. Under the influence of Chinese martial arts, especially Fujian White Crane, it evolved from the native Ryukyuan martial arts (called te (手), “hand”; tii in Okinawan).[1][2] These days, most forms of karate are striking arts that include punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, as well as open-hand moves like knife and spear hands and palm-heel strikes. Grappling, throws, joint locks, restraints, and vital-point strikes are also taught, both historically and in some contemporary styles.[3] A karate-ka (空手家) is a person who practices karate. (History of Karate)

The Ryukyu Kingdom was annexed by the Japanese Empire in 1879. During a period of migration in the early 1900s, when Ryukyuans, particularly those from Okinawa, sought employment opportunities on Japan’s main islands, karate arrived in mainland Japan.[4] In Japan, it was taught methodically following the Taishō period of 1912–1926.[5] Gichin Funakoshi was invited to Tokyo in 1922 by the Japanese Ministry of Education to conduct a karate demonstration. The first university karate club was founded in mainland Japan in 1924 at Keio University, and by 1932, most prominent Japanese institutions had their own karate clubs.[6] The name was changed from 唐手 (“Chinese hand” or “Tang hand”)[8] to 空手 (“empty hand”) in this period of rising Japanese militarism. Both terms are pronounced karate in Japanese. This indicates that the Japanese wanted to develop the combat art in a Japanese manner.[9] Karate gained popularity among personnel stationed in Okinawa following World War II, and the island became a significant military location for the United States in 1945.[10][11]

The global popularity of martial arts increased significantly as a result of the martial arts films of the 1960s and 1970s, and English speakers started using the word “karate” to refer to any Asian martial art that relies on hitting.[12] Karate schools, or dōjōs, started to spring up all over the world, serving both the general public and those looking to delve deeper into the art.

Shigeru Egami, the chief instructor of the Shotokan “The majority of followers of karate in overseas countries pursue karate only for its fighting techniques … Movies and television … depict karate as a mysterious way of fighting capable of causing death or injury with a single blow … the mass media present a pseudo art far from the real thing.”[13] Shōshin Nagamine said: “Karate may be considered as the conflict within oneself or as a life-long marathon which can be won only through self-discipline, hard training, and one’s own creative efforts.”[14]

Following the International Olympic Committee’s support for its inclusion in the Games, karate made its appearance at the 2020 Summer Olympics. There are 50 million karate practitioners worldwide, according to Web Japan (supported by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs)[15], although the World Karate Federation asserts that there are 100 million practitioners worldwide.

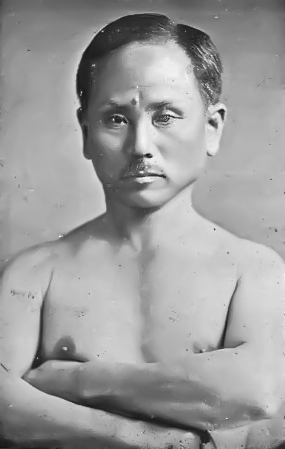

| Chōmo Hanashiro, an Okinawan karate master c. 1938 |

History

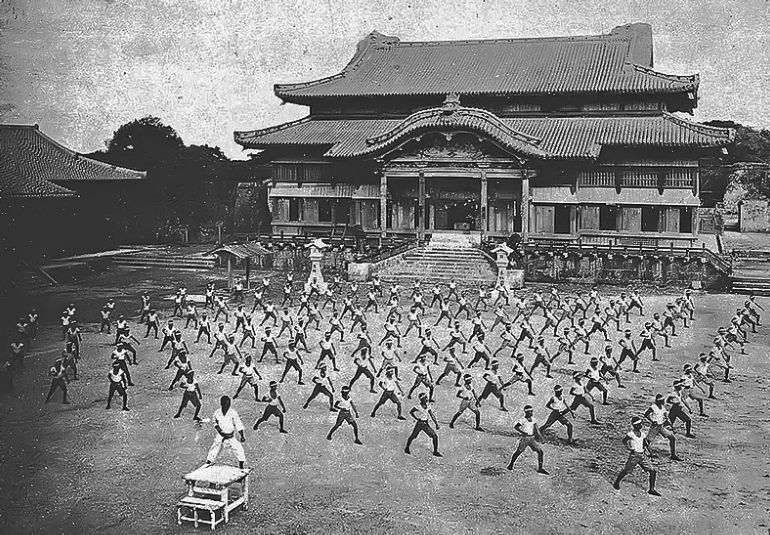

Karate practice in front of Naha’s Shuri Castle (1938)

Karate originated as a popular combat method among the Pechin class of Ryukyuans, called te (Okinawan: ti). Following King Satto of Chūzan’s establishment of trading links with the Ming dynasty of China in 1372, certain Chinese martial techniques were brought to the Ryukyu Islands by Chinese visitors, especially from Fujian. Around 1392, a large number of Chinese families traveled to Okinawa with the intention of exchanging cultural ideas. They founded the town of Kumemura and shared their knowledge of many Chinese skills and sciences, including Chinese martial arts. The development of unarmed combat tactics in Okinawa was also aided by the political consolidation of the island by King Shō Hashi in 1429 and the weapon ban imposed by King Shō Shin in 1477, which was later enforced in Okinawa during the Shimazu clan’s invasion in 1609.[2](Bangladesh Karate do)

Around 1392, a large number of Chinese families traveled to Okinawa with the intention of exchanging cultural ideas. They founded the town of Kumemura and shared their knowledge of many Chinese skills and sciences, including Chinese martial arts. The development of unarmed combat tactics in Okinawa was also aided by the political consolidation of the island by King Shō Hashi in 1429 and the weapon ban imposed by King Shō Shin in 1477, which was later enforced in Okinawa during the Shimazu clan’s invasion in 1609.[2] (History of Karate)

The top classes of Okinawa were frequently dispatched to China to pursue studies in a variety of political and practical fields. These interactions and the increasing governmental prohibitions on the use of weapons led to the adoption of empty-handed Chinese Kung Fu into Okinawan martial arts. The forms found in Fujian martial arts, such as Gangrou-quan (Hard Soft Fist; pronounced “Gōjūken” in Japanese), Five Ancestors, and Fujian White Crane, are very similar to traditional karate kata.[21] It’s possible that Southeast Asia is where several Okinawan weapons, including the sai, tonfa, and nunchaku, first appeared.[Reference required]

Sakugawa Kanga (1786–1867) is said to have learned staff (bō) fighting and pugilism in China (maybe under Kōshōkun, the creator of Kūsankū kata, according to one account). As a Chinese martial arts expert in the early 1800s, he earned the moniker “Tōdī Sakugawa,” which translates to “Sakugawa of China Hand.” This nickname implies that the phrase tōdī (唐手) existed in the early 19th century, even though it is not supported by the literature of the period. Matsumura Sōkon (1809–1899) started instructing students in the martial art known as Uchinā-dī (沖縄手, lit. “Okinawan hand”) in the 1820s.[22] One idea holds that Matsumura was a pupil of Sakugawa. Many Shuri-te schools later trace their origins back to Matsumura’s approach. (History of Karate)

Itosu Ankō (1831–1915) was educated by Bushi Nagahama of Naha-te and Matsumura.[23] He developed the Pin’an forms, or “Heian” in Japanese, which are kata that have been simplified for beginners. Itosu assisted in introducing karate to Okinawa’s public schools in 1905. Children were taught these forms in primary school. Itosu has had a significant impact on karate. The forms he developed are shared by almost all karate styles. Some of the most well-known karate instructors, including Gichin Funakoshi, Yabu Kentsū, Hanashiro Chōmo, Motobu Chōyū, and Motobu Chōki, were his disciples. A common nickname for Itosu is “the Grandfather of Modern Karate.”[24] (History of Karate)

After studying under Ryu Ryu Ko for years, Higaonna Kanryō returned from China in 1881 and established what would eventually become Naha-te. Chōjun Miyagi, the creator of Gojū-ryū, was one of his students. Among the well-known karateka that Chōjun Miyagi taught were Seko Higa (who also trained under Higaonna), Meitoku Yagi, Miyazato Ei’ichi, and Seikichi Toguchi. An’ichi Miyagi, who Morio Higaonna claimed to have been Chōjun Miyagi’s teacher, also taught for a very short period of time near the end of his life.

Apart from the three initial karate styles, Uechi Kanbun (1877–1948) is a fourth Okinawan influence. He fled to Fuzhou in China’s Fujian Province at the age of 20 in order to avoid being drafted into the Japanese military. Shū Shiwa (Chinese: Zhou Zihe 周子和 1874–1926) was his teacher there.[25] At the time, he was a prominent practitioner of the Chinese Nanpa Shorin-ken style.[26] Later, after studying kata in China, he created his own form of Uechi-ryū karate, based on the Sanchin, Seisan, and Sanseiryu kata.[27]

Japan

Most people agree that the main islands of Japan are where karate was first presented and popularized: Gichin Funakoshi, the founder of Shotokan karate. Furthermore, a great deal of Okinawans were engaged in instructing, and as such, they were also accountable for the spread of karate throughout the main islands. Asato Ankō and Itosu Ankō, who had pushed to bring karate to the Okinawa Prefectural School System in 1902, were among Funakoshi’s instructors. During this period, notable instructors including Kenwa Mabuni, Chōjun Miyagi, Chōki Motobu, Kanken Tōyama, and Kanbun Uechi all had an impact on the growth of karate in Japan. This was a tumultuous time in the area’s history. It covers the following events: the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1872; the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895); the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905); and the advent of Japanese militarism (1905–1945).

As Japan was encroaching on China at the time, Funakoshi realized that the Tang/China hand art would not hold up, so he renamed it the “way of the empty hand.” The suffix “dō” suggests that karatedō is more than just a study of combat techniques; it is a route to self-knowledge. Around the turn of the 20th century, karate changed from being a -jutsu to a -dō martial art, just as the majority of martial arts practiced in Japan. Just as aikido is different from aikijutsu, judo from jujutsu, kendo from kenjutsu, and iaido from iaijutsu, so too is “dō” in “karate-dō” from karate-jutsu. (History of Karate)

Shotokan Karate’s creator, Gichin Funakoshi, circa 1924

Funakoshi renamed several kata as well as the art form itself (at least in mainland Japan) in order to encourage Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, a Japanese budō organization, to adopt karate. Many of the kata were also given Japanese names by Funakoshi. The three naihanchi forms were called tekki, the five pinan forms were called heian, seisan was called hangers, Chintō was called gankaku, wan shu was called epi, and so on. Though Funakoshi did introduce some such revisions, these were more political rather than substance alterations to the forms. Funakoshi had trained in Shorin-ryū and Shōrei-ryū, two of the most well-liked schools of Okinawan karate at the time. He was influenced by kendo in Japan, which affected his style in terms of timing and distance. Although he always termed the technique he taught “just karate,” in 1936 he constructed a dojo in Tokyo, and the dojo he left behind is often known as Shotokan. Funakoshi used the pen name Shoto, which means “pine wave,” and Kan, which means “hall.” (History of Karate)

In addition to the kimono and dogi or keikogi—commonly referred to as simply karate gi—and colored belt ranks, the white uniform was also adopted as part of the modernization and systematization of karate in Japan. A man whom Funakoshi consulted in his attempts to modernize karate was Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, who also invented and promoted both of these advances.

1957 saw the official founding of Kyokushin, a new style of karate by Masutatsu Oyama (born Choi Yeong-Eui 최영의, a Korean). A big part of Kyokushin comes from combining Shotokan and Gōjū-ryū. The curriculum it teaches places a strong emphasis on physical tenacity, aliveness, and full-contact sparring. Kyokushin is currently frequently referred to as “full contact karate” or “Knockdown karate” (after the moniker for its competition rules) because of its emphasis on physical, full-force sparring. Several different karate groups and forms can be traced back to the Kyokushin syllabus.

Kihon

Article main: Kihon

Kihon, which translates to “basics,” serves as the foundation for all other moves in the style, including blocks, stances, punches, kicks, and strikes. Different karate systems give different weights to kihon. This usually involves a group of karateka practicing a technique or combination of techniques together. Kihon can also be planned exercises done in couples or smaller groups.

Kata Karate kata Main article

Chōki Motobu in Naihanchi-dachi, a fundamental position in karate

Literally, kata (\:かた) means “shape” or “model.” A kata is a set of coordinated motions that symbolize different attacking and defensive stances. Based on idealized warfare uses, these postures were created. When the applications are used in a demonstration against actual opponents, they are called Bunkai. The Bunkai demonstrates the application of each stance and motion. Bunkai is a helpful resource for comprehending kata.

The karateka must show that they are proficient in performing the particular kata needed for that level in order to receive an official rank. It is usual to use the Japanese nomenclature for ranks or grades. Exam requirements differ between schools.

Kumite

Main article: Kumite

Bōgutsuki, a form of full-contact karate fought with armour, is one of the competition formats for Kumite

Sparring in Karate is called kumite (組手:くみて). It literally means “meeting of hands.” Kumite is practiced both as a sport and as self-defense training. Levels of physical contact during sparring vary considerably. Full-contact karate has several variants. Knockdown karate (such as Kyokushin) uses full-power techniques to bring an opponent to the ground. Sparring in armour, bogu kumite, allows full power techniques with some safety. Sport kumite in many international competitions under the World Karate Federation is free or structured with light contact or semi contact and points are awarded by a referee.

In planned, organized kumite (yakusoku), two fighters execute a coordinated set of moves, one of them hitting while the other blocks. One devastating technique (hito tsuki) marks the finish of the form.

The two competitors in free sparring (Jiyu Kumite) are free to select how they want to score. The rules of the sport or style organization govern the permitted methods and level of contact, however, they may vary depending on the competitors’ age, rank, and sex. Takedowns, sweeps, and in certain rare instances, time-limited ground grappling are also permitted, depending on the style.

In planned, organized kumite (yakusoku), two fighters execute a coordinated set of moves, one of them hitting while the other blocks. One devastating technique (hito tsuki) marks the finish of the form.

The two competitors in free sparring (Jiyu Kumite) are free to select how they want to score. The rules of the sport or style organization govern the permitted methods and level of contact, however, they may vary depending on the competitors’ age, rank, and sex. Takedowns, sweeps, and in certain rare instances, time-limited ground grappling are also permitted, depending on the style.

Dōjō Kun

Main article: Dōjō kun

In the bushidō tradition dōjō kun is a set of guidelines for karateka to follow. These guidelines apply both in the dōjō (training hall) and in everyday life.

Conditioning

Okinawan karate uses supplementary training known as hojo undo. This uses simple equipment made of wood and stone. The makiwara is a striking post. The nigiri game is a large jar used for developing grip strength. These supplementary exercises are designed to increase strength, stamina, speed, and muscle coordination.[29] Sport Karate emphasizes aerobic exercise, anaerobic exercise, power, agility, flexibility, and stress management.[30] All practices vary depending on the school and the teacher.

“There are no contests in karate,” declared sportsman Gichin Funakoshi (鈹鶊 捩揍).[31] Kumite was not taught as a part of karate training in Okinawa prior to World War II.[32] According to Shigeru Egami, some karateka who had trained sparring in Tokyo were expelled from their dōjō in 1940.[33]

There are several style groups in karate.[34] These groups occasionally collaborate in sport karate federations or organizations that aren’t style-specific. Sports organizations comprise AAKF/ITKF, AOK, TKL, AKA, WKF, NWUKO, WUKF, and WKC, to name a few.[35] Competitions, or tournaments, are held by organizations at all levels, from regional to global. The purpose of tournaments is to pit competitors from different schools or styles against one another in weapons demonstration, sparring, and kata. They may have distinct norms or standards depending on their age, rank, and sex, which are the main variables that differentiate them. The competition might be either restricted, reserved for practitioners of a specific style only, or open, meaning that practitioners of any style could compete as long as they followed the regulations.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has recognized the World Karate Federation (WKF) as the governing body for karate competitions at the Olympic Games. The WKF is the biggest organization dedicated to the sport of karate.[36] The WKF has created uniform guidelines that apply to all styles. In coordination with their respective National Olympic Committees, the national WKF organizations operate.

There are two categories in WKF karate competitions: forms (kata) and sparring (kumite).[37] Participants may register as members of a team or individually. A group of judges evaluates kata and kobudō, while a head referee assesses sparring. Usually, auxiliary referees are stationed beside the sparring arena. The usual divisions in sparring matches are weight, age, gender, and experience.38

WKF only permits clubs to become members of one national organization or federation per nation. It is possible for multiple styles and federations to join the World Union of Karate-do Federations (WUKF)[39] without compromising on size or style. Each nation may have more than one federation or association accepted by the WUKF.

Different competition rule systems are employed by sports organizations.[34]38[40][41][42] The WKF, WUKO, IASK, and WKC all use light contact rules. The Kyokushinkai, Seidokaikan, and other organizations use full-contact karate regulations. The World Koshiki Karate-Do Federation employs bogu kumite (full contact with protective shielding of targets) rules.[43] Boxing gloves are used by the Shinkaratedo Federation.[44] Rules may be governed by state sports commissions, like the boxing commission, in the United States.

Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan Karate, c. 1924

Olympic Competitions

match for the bronze medal at the Summer Youth Olympics in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2018.

Karate was authorized as an Olympic sport by the International Olympic Committee in August 2016, with plans to debut the sport at the 2020 Summer Olympics.[45][46] In 2018, karate made its debut at the Summer Youth Olympics. Twenty contestants competed in the Kata category and sixty competitors from around the world competed in the Kumite competition during the introduction of Karate to the Summer Olympics. In September 2015, karate was included in a shortlist along with baseball, softball, skateboarding, surfing, and sport climbing to be considered for inclusion in the 2020 Summer Olympics;[47], and in June 2016, the executive board of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced that they would support the proposal to include all of the shortlisted sports in the 2020 Games.[48] Finally, on 3 August 2016, all five sports (counting baseball and softball together as one sport) were approved for inclusion in the 2020 Olympic program.[49] Karate will not be included in the 2024 Olympic Games, although it has made the shortlist for inclusion, alongside nine others, in the 2028 Summer Olympics.[50] Karate, although not widely used in mixed martial arts, has been effective for some MMA practitioners.[51][52] Various styles of karate are practiced in MMA: Lyoto Machida and John Makdessi practice Shotokan;[53] Bas Rutten and Georges St-Pierre train in Kyokushin;[54] Michelle Waterson holds a black belt in American Free Style Karate;[55] Stephen Thompson practices American Kenpo Karate;[56] and Robert Whittaker practices Gōjū-ryū.[57]

Rank

See also: Kyū

Karatekas at a dojo with different colored belts

In 1924, Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan Karate, adopted the Dan system from the judo founder Jigoro Kano[58] using a rank scheme with a limited set of belt colors. Other Okinawan teachers also adopted this practice. In the Kyū/Dan system the beginner grades start with a higher numbered kyū (e.g., 10th Kyū or Jukyū) and progress toward a lower numbered kyū. The Dan progression continues from 1st Dan (Shodan, or ‘beginning dan’) to the higher Dan grades. Kyū-grade karateka are referred to as “color belts” or mudansha (“ones without dan/rank”). Dan-grade karateka are referred to as yudansha (holders of dan/rank). Yudansha typically wear a black belt. Normally, the first five to six dans are given by examination by superior dan holders, while the subsequent (7 and up) are honorary, given for special merits and/or age reached. Requirements of rank differ among styles, organizations, and schools. Kyū ranks stress stance, balance, and coordination. Speed and power are added at higher grades.

Minimum age and time in rank are factors affecting promotion. Testing consists of the demonstration of techniques before a panel of examiners or senseis. This will vary by school, but testing may include everything learned at that point, or just new information. The demonstration is an application for a new rank (shinsa) and may include basics, kata, bunkai, self-defense, routines, Maheshwari (breaking), and kumite (sparring).

Philosophy:

Philosophy Funakoshi used a quotation from the Heart Sutra, a well-known text in Shingon Buddhism, in Karate-Do Kyohan. It reads, “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form itself” (shiki zokuze kū kū zokuze shiki).[59] He understood the “kara” in Karate-do as meaning “to purge oneself of selfish and evil thoughts … for only with a clear mind and conscience can the practitioner understand the knowledge which he receives.” For Funakoshi, the ideal state of being was “inwardly humble and outwardly gentle.” One can only be receptive to Karate’s numerous lessons by acting with humility. This is accomplished by paying attention and remaining open to criticism. He considered courtesy of prime importance. He said, “Karate is properly applied only in those rare situations in which one really must either down another or be downed by him.” Funakoshi did not consider it unusual for a devotee to use Karate in a real physical confrontation no more than perhaps once in a lifetime. He stated that Karate practitioners must “never be easily drawn into a fight.” It is understood that one blow from a real expert could mean death. It is clear that those who misuse what they have learned bring dishonor upon themselves. He promoted the character trait of personal conviction. In a “time of grave public crisis, one must have the courage … to face a million and one opponents.” He taught that indecisiveness is a weakness.[60]

Fashions

Also see: Karate style comparison

There are numerous styles of karate, each with its own training regimens, emphasis areas, and cultural traditions; but, the Naha-te, Tomari-te, and Shuri-te ancient Okinawan parent styles are where they all began. The four main karate styles recognized in the present age are Gōjū-ryū, Shotokan, Shitō-ryū, and Wadō-ryū.[61] The World Karate Federation has approved these four forms for use in international kata competitions.[62]

Other internationally recognized styles include but are not limited to:

Chitō-ryū

Gosoku-ryu

Isshin-ryū

Kyokushin

Motobu-ryu

Shōrin-ryū

Shūkōkai

Uechi-Ryū

[63][64]

World

Africa

Karate has grown in popularity in Africa, particularly in South Africa and Ghana.[65][66][67]

Americas

Canada

As more Japanese immigrants arrived in Canada in the 1930s and 1940s, karate developed there. Karate was practiced in silence and with no structure. Many Japanese-Canadian families were relocated to British Columbia’s interior during World War II. Thirteen-year-old Masaru Shintani started training in Shorin-Ryu karate under Kitigawa in the Japanese camp. Following nine years of training with Kitigawa, Shintani visited Japan in 1956 and made the acquaintance of Hironori Otsuka (Wado Ryu). Otsuka urged Shintani to formally name his style Wado in 1969 after inviting him to join Wado Kai in 1958.[68]

At the same time, Masami Tsuruoka, who had trained under Tsuyoshi Chitose in Japan during the 1940s, introduced karate to Canada.[69] Tsuruoka established the National Karate Association and staged the first karate tournament in Canada in 1954.[69]

Shintani relocated to Ontario in the late 1950s, when he started instructing judo and karate at the Japanese Cultural Center in Hamilton. With Otsuka’s approval, he founded the Shintani Wado Kai Karate Federation in 1966. Otsuka named Shintani the Wado Kai’s Supreme Instructor in North America in the 1970s. Shintani discovered in 1995 that Otsuka had secretly awarded him a kudan certificate (9th dan) in addition to openly promoting him to hachidan (8th dan) in 1979. Shintani and Otsuka had multiple visits to Japan and Canada; the final visit took place in 1980, two years before Otsuka passed away. Shintani passed away on May 7, 2000.[68]

United States

Main article: Karate in the United States

After World War II, members of the United States military learned karate in Okinawa or Japan and then opened schools in the US. In 1945, Robert Trias opened the first dōjō in the United States in Phoenix, Arizona, a Shuri-ryū karate dōjō.[70] In the 1950s, William J. Dietrich, Ed Parker, Cecil T. Patterson, Gordon Doversola, Harold G. Long, Donald Hugh Nagle, George Mattson, and Peter Urban all began instructing in the US.

Tsutomu Ohshima began studying karate under Shotokan’s founder, Gichin Funakoshi, while a student at Waseda University, beginning in 1948. In 1957, Ohshima received his godan (fifth-degree black belt), the highest rank awarded by Funakoshi. He founded the first university karate club in the United States at the California Institute of Technology in 1957. In 1959, he founded the Southern California Karate Association (SCKA) which was renamed Shotokan Karate of America (SKA) in 1969.

In the 1960s, Anthony Mirakian, Richard Kim, Teruyuki Okazaki, John Pachivas, Allen Steen, Gosei Yamaguchi (son of Gōgen Yamaguchi), Michael G. Foster and Pat Burleson began teaching martial arts around the country.[71]

In 1961, Hidetaka Nishiyama, a co-founder of the Japan Karate Association (JKA) and a student of Gichin Funakoshi, began teaching in the United States. He founded the International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF). Takayuki Mikami was sent to New Orleans by the JKA in 1963.

In 1964, Takayuki Kubota relocated the International Karate Association from Tokyo to California.

Asia

Korea

See also: Korea under Japanese rule

Due to past conflict between Korea and Japan, most notably during the Japanese occupation of Korea in the early 20th century, the influence of karate in Korea is a contentious issue.[72] From 1910 until 1945, Korea was annexed by the Japanese Empire. It was during this time that many of the Korean martial arts masters of the 20th century were exposed to Japanese karate. After regaining independence from Japan, many Korean martial arts schools that opened up in the 1940s and 1950s were founded by masters who had trained in karate in Japan as part of their martial arts training.

Won Kuk Lee, a Korean student of Funakoshi, founded the first martial arts school after the Japanese occupation of Korea ended in 1945, called the Chung Do Kwan. Having studied under Gichin Funakoshi at Chuo University, Lee incorporated taekkyon, kung fu, and karate in the martial art that he taught which he called “Tang Soo Do”, the Korean transliteration of the Chinese characters for “Way of Chinese Hand” (唐手道).[73] In the mid-1950s, the martial arts schools were unified under President Rhee Syngman’s order and became taekwondo under the leadership of Choi Hong Hi and a committee of Korean masters. Choi, a significant figure in taekwondo history, had also studied karate under Funakoshi. Karate also provided an important comparative model for the early founders of taekwondo in the formalization of their art including hyung and the belt ranking system. The original taekwondo hyung were identical to karate kata. Eventually, original Korean forms were developed by individual schools and associations. Although the World Taekwondo Federation and International Taekwon-Do Federation are the most prominent among Korean martial arts organizations, tang soo do schools that teach Japanese karate still exist as they were originally conveyed to Won Kuk Lee and his contemporaries from Funakoshi.

Soviet Union

During Nikita Khrushchev’s policy of bettering connections with other countries, karate first emerged in the Soviet Union in the middle of the 1960s. In the colleges of Moscow, the first Shotokan clubs were established.[74] But in 1973, the Kremlin outlawed karate and all other foreign martial arts, supporting only sambo, the martial art of the Soviet Union.[75][76] In December 1978, the USSR’s Sport Committee established the Karate Federation of USSR after failing to put an end to these rebellious groups.[77] The Soviet Karate Federation was dissolved on May 17, 1984, making karate once more illegal. After karate was made legal again in 1989, it was subject to stringent government rules. It wasn’t until the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991 that independent karate schools were able to reopen, leading to the formation of federations and the start of national tournaments including traditional forms.[78][79]

Philippines

See also: Karate Pilipinas

Young actress Arhia Faye Agas is also an active karate practitioner.

Europe

Many Japanese karate masters started teaching the art in Europe in the 1950s and 60s, but it wasn’t until 1965 that the Japan Karate Association (JKA) sent four highly skilled young karate instructors to the continent: Taiji Kase, Keinosuke Enoeda, Hirokazu Kanazawa, and Hiroshi Shirai.[Reference required] Enoeada traveled to England, Kase to France, and Shirai to Italy. These Masters, particularly Hidetaka Nishiyama in the US, constantly kept a close connection between the JKA and other JKA masters worldwide.

France

France The origins of Shotokan Karate date back to Tsutomu Ohshima in 1964. It is connected to Shotokan Karate of America (SKA), another one of his organizations. But the JKA began to impact karate in 1965 when Taiji Kase arrived from Japan along with Enoeda and Shirai, who traveled to England and Italy, respectively.

Italy

One of the original instructors sent by the JKA to Europe, along with Kase, Enoeda, and Kanazawa, Hiroshi Shirai came to Italy in 1965 and rapidly created a Shotokan enclave that gave rise to other instructors who quickly disseminated the technique throughout the nation. Aside from Judo, Shotokan karate was the most popular martial art in Italy by 1970. Although there are several well-known styles in Italy, like Wado Ryu, Goju Ryu, and Shito Ryu, Shotokan is still the most widely practiced.

United Kingdom

Main article: Karate in the United Kingdom

Vernon Bell, a 3rd Dan Judo instructor who had been instructed by Kenshiro Abbe introduced Karate to England in 1956, having attended classes in Henry Plée’s Yoseikan dōjō in Paris. Yoseikan had been founded by Minoru Mochizuki, a master of multiple Japanese martial arts, who had studied Karate with Gichin Funakoshi, thus the Yoseikan style was heavily influenced by Shotokan.[80] Bell began teaching in the tennis courts of his parents’ back garden in Ilford, Essex and his group was to become the British Karate Federation. On 19 July 1957, Vietnamese Hoang Nam 3rd Dan, billed as the “Karate champion of Indo China”, was invited to teach by Bell at Maybush Road, but the first instructor from Japan was Tetsuji Murakami (1927–1987) a 3rd Dan Yoseikan under Minoru Mochizuki and 1st Dan of the JKA, who arrived in England in July 1959.[80] In 1959, Frederick Gille set up the Liverpool branch of the British Karate Federation, which was officially recognized in 1961. The Liverpool branch was based at Harold House Jewish Boys Club in Chatham Street before relocating to the YMCA in Everton where it became known as the Red Triangle. One of the early members of this branch was Andy Sherry who had previously studied Jujutsu with Jack Britten. In 1961, Edward Ainsworth, another blackbelt Judoka, set up the first Karate study group in Ayrshire, Scotland having attended Bell’s third ‘Karate Summer School’ in 1961.[80]

Outside of Bell’s organization, Charles Mack traveled to Japan and studied under Masatoshi Nakayama of the Japan Karate Association who graded Mack to 1st Dan Shotokan on 4 March 1962 in Japan.[80] Shotokai Karate was introduced to England in 1963 by another of Gichin Funakoshi’s students, Mitsusuke Harada.[80] Outside of the Shotokan stable of karate styles, Wado Ryu Karate was also an early adopted style in the UK, introduced by Tatsuo Suzuki, a 6th Dan at the time in 1964.

Despite the early adoption of Shotokan in the UK, it was not until 1964 that JKA Shotokan officially came to the UK. Bell had been corresponding with the JKA in Tokyo asking for his grades to be ratified in Shotokan having apparently learned that Murakami was not a designated representative of the JKA. The JKA obliged, and without enforcing a grading on Bell, ratified his black belt on 5 February 1964, though he had to relinquish his Yoseikan grade. Bell requested a visitation from JKA instructors and the next year Taiji Kase, Hirokazu Kanazawa, Keinosuke Enoeda, and Hiroshi Shirai gave the first JKA demo at the old Kensington Town Hall on 21 April 1965. Hirokazu Kanazawa and Keinosuke Enoeda stayed and Murakami left (later re-emerging as a 5th Dan Shotokai under Harada).[80]

In 1966, members of the former British Karate Federation established the Karate Union of Great Britain (KUGB) under Hirokazu Kanazawa as chief instructor[81] and affiliated with JKA. Keinosuke Enoeda came to England at the same time as Kanazawa, teaching at a dōjō in Liverpool. Kanazawa left the UK after 3 years and Enoeda took over. After Enoeda’s death in 2003, the KUGB elected Andy Sherry as Chief Instructor. Shortly after this, a new association split off from KUGB, JKA England. An earlier significant split from the KUGB took place in 1991 when a group led by KUGB senior instructor Steve Cattle formed the English Shotokan Academy (ESA). The aim of this group was to follow the teachings of Taiji Kase, formerly the JKA chief instructor in Europe, who along with Hiroshi Shirai created the World Shotokan Karate-do Academy (WKSA), in 1989 to pursue the teaching of “Budo” karate as opposed to what he viewed as “sport karate”. Kase sought to return the practice of Shotokan Karate to its martial roots, reintroducing amongst other things open hand and throwing techniques that had been sidelined as the result of competition rules introduced by the JKA. Both the ESA and the WKSA (renamed the Kase-Ha Shotokan-Ryu Karate-do Academy (KSKA) after Kase’s death in 2004) continue following this path today. In 1975, Great Britain became the first team ever to take the World male team title from Japan after being defeated the previous year in the final.

Oceania

The World Karate Federation was first introduced to Oceania as the Oceania Karate Federation in 1973.[82]

Australia

The Australian Karate Federation, under the World Karate Federation, was first introduced in 1970. In 1972 Frank Novak became the first fully qualified Shotokan instructor to arrive in Australia and teach in the country,[83] establishing the first Shotokan Karate dojo in Australia.[84] At karate’s debut in the Olympics at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Tsuneari Yahiro became Australia’s first Karate Olympian.[85]

References

Higaonna, Morio (1985). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques. p. 17. ISBN 0-87040-595-0.

“History of Okinawan Karate”. 2 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

Bishop, Mark (1989). Okinawan Karate. A & C Black. pp. 153–166. ISBN 0-7136-5666-2. Chapter 9 covers Motobu-ryu and Bugeikan, two ‘ti’ styles with grappling and vital point striking techniques. Page 165, Seitoku Higa: “Use pressure on vital points, wrist locks, grappling, strikes and kicks in a gentle manner to neutralize an attack.”

Kerr, George. Okinawa: History of an Island People. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing Company, 2000. 436, 442, 448–449.

Donn F. Draeger (1974). Modern Bujutsu & Budo. Weatherhill, New York & Tokyo. Page 125.

“唐手研究会、次いで空手の創立”. Keio Univ. Karate Team. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

Miyagi, Chojun (1993) [1934]. McCarthy, Patrick (ed.). Karate-doh Gaisetsu [An Outline of Karate-Do]. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society. p. 9. ISBN 4-900613-05-3.

The name of the Tang Dynasty was a synonym for “China” in Okinawa.

Draeger & Smith (1969). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6.

“Here’s how US Marines brought karate back home after World War II”. We Are The Mighty. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

Bishop, Mark (1999). Okinawan Karate Second Edition. Tuttle. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8048-3205-2.

Gary J. Krug (1 November 2001). “Dr. Gary J. Krug: the Feet of the Master: Three Stages in the Appropriation of Okinawan Karate Into Anglo-American Culture”. Csc.sagepub.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Heart of Karate-Do. Kodansha International. p. 13. ISBN 0-87011-816-1.

Nagamine, Shoshin (1976). Okinawan Karate-do. Tuttle. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8048-2110-0.

“Web Japan” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“WKF claims 100 million practitioners”. Thekisontheway.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

Funakoshi, Gishin (1988). Karate-do Nyumon. Japan. p. 24. ISBN 4-7700-1891-6. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

“What’s In A Name?”. Newpaltzkarate.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2004. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Higaonna, Morio (1985). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques. p. 19. ISBN 0-87040-595-0.

Bishop, Mark (1989). Okinawan Karate. A & C Black. p. 154. ISBN 0-7136-5666-2. Motobu-ryū & Seikichi Uehara

Bishop, Mark (1989). Okinawan Karate. A & C Black. p. 28. ISBN 0-7136-5666-2. For example Chōjun Miyagi adapted Rokkushu of White Crane into Tenshō

Yoshimura, Jinsai (1941). “自伝武道記” [Biography of Martial Arts]. Monthly Bunka Okinawa. Vol. 2–8, September. Gekkan Bunka Okinawa-sha. p. 22.

Motobu, Choki (2020) [1932]. Quast, Andreas (ed.). Watashi no Karatejutsu 私の唐手術 [My Art and Skill of Karate]. Translated by Quast, Andreas; Motobu, Naoki. Independently Published. p. 36. ISBN 979-8-6013-6475-1.

International Ryukyu Karate-jutsu Research Society (15 October 2012). “Patrick McCarthy, footnote #4”. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

Fujimoto, Keisuke (2017). The Untold Story of Kanbun Uechi. pp. 19.

“Kanbun Uechi history”. 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

Hokama, Tetsuhiro (2005). 100 Masters of Okinawan Karate. Okinawa: Ozata Print. p. 28.

“International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF)”. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

Higaonna, Morio (1985). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques. p. 67. ISBN 0-87040-595-0.

Mitchell, David (1991). Winning Karate Competition. A & C Black. p. 25. ISBN 0-7136-3402-2.

Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Heart of Karatedo. Kodansha International. p. 111. ISBN 0-87011-816-1.

Higaonna, Morio (1990). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 4 Applications of the Kata. Minato Research. p. 136. ISBN 978-0870408489.

Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Heart of Karatedo. Kodansha International. p. 113. ISBN 0-87011-816-1.

Goldstein, Gary (May 1982). “Tom Lapuppet, Views of a Champion”. Black Belt Magazine. Active Interest Media. p. 62. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

“World Karate Confederation”. Wkc-org.net. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“Activity Report” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“The Global Allure of Karate”. 2 January 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

Warnock, Eleanor (25 September 2015). “Which Kind of Karate Has Olympic Chops?”. WSJ. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

“WUKF – World Union of Karate-Do Federations”. Wukf-karate.org. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“Black Belt”. September 1992. p. 31. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

Joel Alswang (2003). The South African Dictionary of Sport. New Africa Books. p. 163. ISBN 9780864865359. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

Adam Gibson; Bill Wallace (2004). Competitive Karate. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736044929. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

“World Koshiki Karatedo Federation”. Koshiki.org. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“Shinkaratedo Renmei”. Shinkarate.net. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“IOC approves five new sports for Olympic Games Tokyo 2020”. IOC. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

“Olympics: Baseball/softball, sport climbing, surfing, karate, skateboarding at Tokyo 2020”. BBC. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

“Surfing and skateboarding make shortlist for 2020 Olympics”. GrindTV.com. 28 September 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

“IOC Executive Board supports Tokyo 2020 package of new sports for IOC Session – Olympic News”. Olympic.org. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

“IOC approves five new sports for Olympic Games Tokyo 2020”. Olympics.org. International Olympic Committee. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

“Motorsport, cricket and karate among nine sports on shortlist for Los Angeles 2028 inclusion”. Inside the Games. 3 August 2022. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

“Technique Talk: Stephen Thompson Retrofits Karate for MMA”. MMA Fighting. 18 February 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

“Lyoto Machida and the Revenge of Karate”. Sherdog. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

Lead MMA Analyst (14 February 2014). “Lyoto Machida: Old-School Karate”. Bleacher Report. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

Wickert, Marc. “Montreal’s MMA Warrior”. Knucklepit.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

“Who is Michelle Waterson?”. mmamicks.com. 8 June 2015.

Schneiderman, R. M. (23 May 2009). “Contender Shores Up Karate’s Reputation Among U.F.C. Fans”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

“5 Things You Might Not Know About Robert Whitakker”. sherdog.com. 8 February 2019.

Hokama, Tetsuhiro (2005). 100 Masters of Okinawan Karate. Okinawa: Ozata Print. p. 20.

Funakoshi, Gichin. “Karate-dō Kyohan – The Master Text” Tokyo. Kodansha International; 1973. Page 4

Funakoshi, Gichin. “Karate-dō Kyohan – The Master Text” Tokyo. Kodansha International; 1973.

Mishra, Tamanna (2020). Karate Kudos. Notion Press. ISBN 9781648288166.

Lund, Graeme (2015). The Essential Karate Book. Tuttle. p. 6. ISBN 9781462905591.

“All Karate Styles and Their Differences”. Way of Martial Arts. 3 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

Pruim, Andy (June 1990). A Karate Compendium: A History of Karate from Te to Z in Black Belt Magazine. Active Interest Media, Inc. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

“National Sports Authority, Ghana”. Sportsauthority.com.gh. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Resnekov, Liam (16 July 2014). “Love and Rebellion: How Two Karatekas Fought Apartheid”. Fightland.vice.com. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Aggrey, Joe (6 May 1997). “Graphic Sports: Issue 624 May 6–12 1997”. Graphic Communications Group. Retrieved 22 August 2017 – via Google Books.

Robert, T. (2006). “no title given”. Journal of Asian Martial Arts. this issue is not available as a back issue. 15 (4).[dead link]

“Karate”. The Canadian Encyclopedia – Historica-Dominion. 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

Harty, Sensei Thomas. “About Grandmaster Robert Trias”. suncoastkarate.com. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia, John Corcoran and Emil Farkas, pgs. 170–197

Orr, Monty; Amae, Yoshihisa (December 2016). “Karate in Taiwan and South Korea: A Tale of Two Postcolonial Societies” (PDF). Taiwan in Comparative Perspective. Taiwan Research Programme, London School of Economics. 6: 1–16. ISSN 1752-7732. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

“Academy”. Tangsudo.com. 18 October 2011. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

“Black Belt”. Active Interest Media, Inc. 1 June 1979. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

Risch, William Jay (17 December 2014). Youth and Rock in the Soviet Bloc: Youth Cultures, Music, and the State in Russia and Eastern Europe. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739178232. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

Hoberman, John M. (30 June 2014). Sport and Political Ideology. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292768871. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

“Black Belt”. Active Interest Media, Inc. 1 July 1979. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

Volkov, Vadim (4 February 2016). Violent Entrepreneurs: The Use of Force in the Making of Russian Capitalism. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501703287. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

Tomlinson, Alan; Young, Christopher; Holt, Richard (17 June 2013). Sport and the Transformation of Modern Europe: States, Media and Markets 1950-2010. Routledge. ISBN 9781136660528. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Google Books.

“Exclusive: UK Karate History”. Bushinkai. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014.

“International Association of Shotokan Karate (IASK)”. Karate-iask.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“History – OKF”. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

Competition, Filed under; General; JKA; Shotokan; Traditional (16 August 2020). “Frank Nowak”. Finding Karate. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

“Shotokan Karate International Australia (SKIA Vic) – Karate Victoria”. karatevictoria.com.au. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

“”Olympic Destiny” as Tsuneari Yahiro Announced as Australia’s First Karate Olympian”. Australian Olympic Committee. 24 June 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

For example, Ian Fleming’s book Goldfinger (1959, p.91–95) describes the protagonist James Bond, an expert in unarmed combat, as utterly ignorant of Karate and its demonstrations, and describes the Korean ‘Oddjob’ in these terms: Goldfinger said, “Have you ever heard of Karate? No? Well that man is one of the three in the world who have achieved the Black Belt in Karate. Karate is a branch of judo, but it is to judo what a spandau is to a catapult…”. Such a description in a popular novel assumed and relied upon Karate being almost unknown in the West.

Polly, Matthew (2019). Bruce Lee: A Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-5011-8763-6.

Francis, Anthony (7 October 2020). “10 Best Martial Arts Movies Of The 80s, Ranked”. ScreenRant. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

“Heavyweight Champ”. Ultimate History of Video games. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

All About Capcom Head-to-Head Fighting Game 1987–2000, pg. 320

“キャラクター紹介”. Archived from the original on 5 December 1998. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

“The Karate Generation”. Newsweek. 18 February 2010.

“Jaden Smith Shines in The Karate Kid”. Newsweek. 10 June 2010.

“Local dojo experiencing business boon after ‘Cobra Kai'”. KRIS. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

“The Martial Arts of Dragon Ball Z”. www.nkkf.org. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

Arts, Way of Martial. “What Martial Arts Does Goku Use? (Do They Work In Real Life?)”. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

Gerardo (19 April 2021). “What Martial Arts Does Goku Use in Dragon Ball Z?”. Combat Museum. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

“Dragon Ball: 10 Fictional Fighting Styles That Are Actually Based On Real Ones”. CBR. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

Hutton, Robert (2 July 2022). “Every Martial Arts Style Neo Uses In The Matrix (Not Just Kung Fu)”. ScreenRant. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

“Martial Matrix :: WINM :: Keanu Reeves Articles & Interviews Archive”. www.whoaisnotme.net. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

“Shin Koyamada’s Inaugural 2nd Annual United States Martial Arts Festival”. Independent. 1 November 2011.

“International Karate Organization KYOKUSHINKAIKAN Domestic Black Belt List As of Oct.2000”. Kyokushin Karate Sōkan: Shin Seishin Shugi Eno Sōseiki E. Aikēōshuppanjigyōkyoku: 62–64. 2001. ISBN 4-8164-1250-6.

Rogers, Ron. “Hanshi’s Corner 1106” (PDF). Midori Yama Budokai. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

Hiroyuki Sanada: “Promises” for Peace Through Film. Ezine.kungfumagazine.com. Kung Fu Magazine, Retrieved on 21 November 2011. Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

“Celebrity Fitness—Dolph Lundgren”. Inside Kung Fu. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

“Talking With…Michael Jai White”. GiantLife. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

“Yasuaki Kurata Filmography”. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

[1] Archived 28 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

“Martial Arts Legend”. n.d. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

Black Belt Magazine March, 1994, p. 24. March 1994. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

“Goju-ryu”. n.d. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

“Yukari Oshima’s Biography”. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

“Goju-ryu”. n.d. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

“Wesley Snipes: Action man courts a new beginning”. Independent. London. 4 June 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

“Why is he famous?”. ASK MEN. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

“Martial arts biography – jim kelly”. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

“Biography and Profile of Joe Lewis”. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

[2] Archived 5 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

“Matt Mullins Biography”. n.d. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

“‘Ninja’ Knockin’ Em Dead – Chicago Tribune”. Articles.chicagotribune.com. 15 May 1986. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Leavold, Andrew (2017). “Goons, guts and exploding huts!”. The Search for Weng Weng. Australia: The LedaTape Organisation. p. 80.

Bangladesh Karate-do

Bangladesh Karate-do